Year after year, the field of digital forensics and incident response (DFIR) presents us with new challenges. Various vendors from around the world are tirelessly striving to simplify and enhance the work of experts in this field, but there are some things you probably do not know about (or simply never paid attention to) that we discussed in the first part of these series. Today we’ll discuss some real cases to shed light onto some vendors’ shady practices.

The yellow leader’s T-Shirt

One striking observation is the prevalence of self-proclaimed leaders among these vendors. It’s fascinating to see the consistent use of grandiose titles in their press releases. Almost every company claims to be the “global leader” or “industry’s leading provider” in digital forensics and intelligence solutions. I absolutely love this; here are some real quotes from press-releases of different vendors:

- Company A, the global leader in Digital Intelligence Solutions…

- Company B, a global leader in forensic technology for mobile device investigations…

- Company C is a global leader in digital forensics technology…

- Company D, a global leader in digital forensics for law enforcement…

- Company E, the industry’s leading provider of digital forensic investigation technology…

- Company F is a world leader in forensic technology…

- Company G is a global leader in digital forensics software.

- Company H is a leading provider of mobile device digital forensics.

There is one vendor that stands out from the crowd, and they have earned immense respect from us precisely because they refrain from such self-promotion. They must be the real leader after all:

“Founded in 2010, Magnet Forensics is a developer of digital investigation software that acquires, analyzes, reports on, and manages evidence from digital sources, including computers, mobile devices, IoT devices and cloud services.”

Secrets are lies by another name

Another intriguing aspect pertains to the secrecy surrounding certain products. Some vendors require customers to sign nondisclosure agreements (NDAs), preventing discussions about sensitive topics such as the capabilities of their products.

No discussion of sensitive topics commonly protected by NDA such as PRODUCT’s capabilities.

Can you imagine that the features and capabilities of a tool are protected with a NDA? The reasons behind such restrictions may vary. One motive could be the desire to conceal vulnerabilities. In the past, a software vendor revealed that wide disclosure had led to severe repercussions, prompting Apple to restrict certain forensic capabilities. Another reason could be the fear of competitors gaining access to valuable information, potentially resulting in stolen ideas or advantages. Here is what we one software vendor told us in a comment to our blog article:

There have been cases where that wide disclosure policy has caused severe implications and responses from Apple’s side – directly causing the unfortunate shut down of capabilities the forensics community had before the disclosure.

However, the true motivations for these NDAs are likely different. Vendors are primarily focused on selling licenses, preferably through long-term contracts, with the expectation that customers will eventually become accustomed to the limitations imposed. In our view, the entire “they’ll get used to it because the choice of available tools in the field is limited” approach is borderline bait-and-switch tactics.

Anyways, whatever the reasons are, the complete product specifications, including a comprehensive list of supported devices, detailed extraction and recovery methods, and any limitations, are often withheld. All you get is some marketing descriptions such as “Advanced strategy 1” or “Supersonic brute-force” without a mention of any specific requirements or limitations. In some cases, even after acquiring a license, customers may still find themselves lacking vital information, unless they attend expensive courses that may cost more than the license itself.

Need for speed

When it comes to passcode cracking, the lack of transparency becomes even more apparent. Most vendors avoid publicly disclosing the speed at which their tools can crack passcodes. Instead, they use terms like “brute force,” “supersonic brute force,” “SE-bound fast brute force,” and “Brute Force Turbo Boost v2.” The only numbers provided are often framed in comparisons, such as “6-digit passcodes in under 24 hours (other vendors ~25 years)” or “Can Brute Force 6-digits in 6 months”.

It is evident that obtaining accurate and comprehensive information about passcode cracking speeds is quite challenging. In case if you are curios, “supersonic” brute-force is slightly above 5,000 APD (Attempts Per Day); I am not saying this speed is bad (especially as most other vendors cannot do that at all), but I definitely would not call it “supersonic”.

Juggling with Numbers

The bigger, the better! In product descriptions, you have probably come across texts like this:

Version X.Y supports over N device models, more than M application versions, and P cloud services.

The numbers are staggering, reaching tens of thousands. However, upon closer inspection, one thing becomes clearly apparent: the so-called “different” device models are in fact a number of nearly identical models. The inflated numbers account for every variations like memory capacity or color (they do receive different model identifiers).

The intrigue develops to the count of supported apps, where every version ever released counts, even if the data format remained unchanged. The same goes for cloud services – for example, some manufacturers count a dozen “different” services from a single Apple iCloud service, considering each data category like contacts or calendars as separate services.

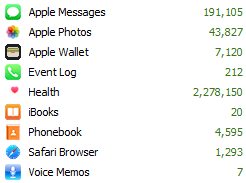

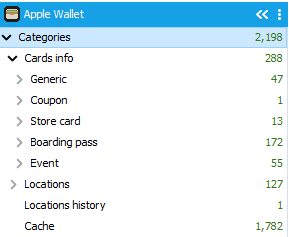

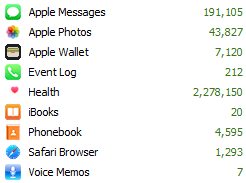

When it comes to artifacts, things get even more amusing. For instance, while reviewing the backup contents of my iPhone in one of the products, I came across some 7,000 Apple Wallet artifacts:

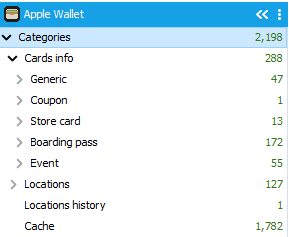

When I examined them closer, the counter displayed a significantly lower number, but even there, the data was heavily inflated (the actual number of records was less than 300):

The same approach is often applied to data from other applications – practically any data and files, no matter how meaningless or useless, are considered “artifacts.”

Such exaggerations significantly hinder the customers’ ability to correctly assess whether all the data has been extracted and analyzed. It becomes even more challenging to verify the results by comparing what different programs yield. One product shows 7,120 “artifacts” in a certain category, while another might display two thousand, and yet another product displays only 288 (based on the actual number of records). Evaluating which product has performed more accurately is nearly impossible, thanks to these “inflations.”

The first and only

We all love Apple’s presentations with all these “amazing”, “exciting”, “incredible” and so on. But there is only one Apple.

In the highly competitive world of digital forensics, vendors constantly strive to be at the forefront, claiming to be innovative and the first to introduce groundbreaking features. However, the reality doesn’t always align with these vendors’ claims. It is not uncommon to witness conflicts on social media platforms like Twitter and LinkedIn, where one company touts a supposedly revolutionary new feature, only to be countered by another company claiming they had already implemented it years ago. The race to be first can lead to dubious claims and attempts to redefine innovation to fit marketing narratives.

Once upon a time I experienced a similar thing. One company publicly claimed that they were those who invented “cloud forensics”. I was really surprised as we were the first (indeed) who released iCloud acquisition software over 10 years ago; so I wrote personally to their marketing director, and reminded her about that. “Yes, I know that”, she replied, “but we support more cloud sources, so our software deserves the ‘first’ anyway”. Oh, never mind.

Another company decided to advertise that they were the second who implemented a certain feature. So what? Does that mean that a potential customer should first try the solution of the company who claims to be the first, and if they don’t like it for some reason, pick the next one who was the second? Seriously?

Innovations and limitations

Occasionally, vendors overstate the capabilities of their products in press releases, leaving out critical limitations. I recall one mobile forensic company’s press release from 2017, boldly stating that they had “overcome data encryption on Android devices” and had “gained direct access to complete user data even if it was previously deleted” that made their tool “the most complete and up-to-date password recovery and decryption solutions for Android devices”. However, upon closer examination, it became apparent that these claims were applicable only to select smartphone models from a single manufacturer and were subject to several limitations. While still an impressive feature, it fell short of the lofty promises made in the press release.

In general, marketing materials naturally tend to downplay or omit limitations altogether. Sometimes, a product manual may contain fine print detailing certain conditions, but uncovering the complete list of supported models, operating system and application versions, and other critical details can be a daunting task.

Back to the “innovations”, my favorite is the dark theme support. That’s obvious that no forensic expert can live without it, right?

Genuine innovations in the DFIR field are few and far between. Examples include MSAB‘s app downgrade extraction method and the checkm8 exploit, which, although not attributed to any specific forensic vendor, has had a significant impact. Some vendors may offer exciting features in their premium versions, but they rarely disclose the specifics.

License to kill

Licensing terms for forensic software are often unclear, leaving users in a state of uncertainty. When a license expires, the software may either cease functioning entirely or severely limit its capabilities, forcing users into read-only mode or preventing them from saving reports. Remembering to renew licenses on time can be challenging, and failing to do so can lead to unfavorable consequences. Moreover, it has been reported that some vendors retain the right to terminate licenses under certain circumstances, such as suspected illegal use or compliance with court orders or legislation.

The user agreement for the company’s products mentions a “Disabling code”, and claims COMPANY retains the right to remotely shut down its devices if it believes the customer is using them illegally, or following a court order or legislation.

However, sources suggest that “using the devices illegally” and “court order” are not the only factors that can lead to license termination.

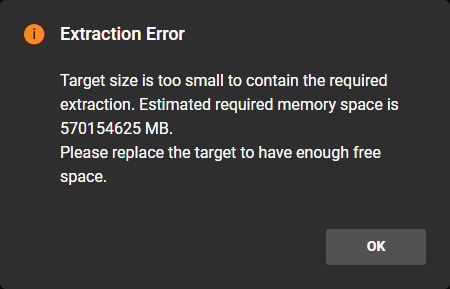

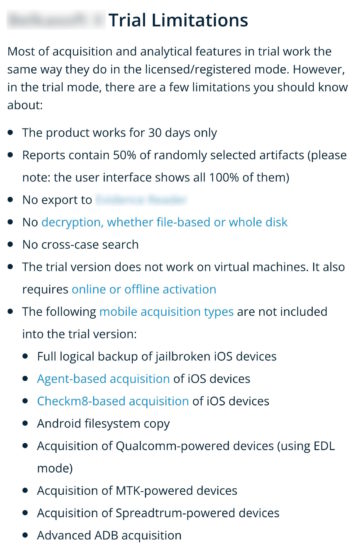

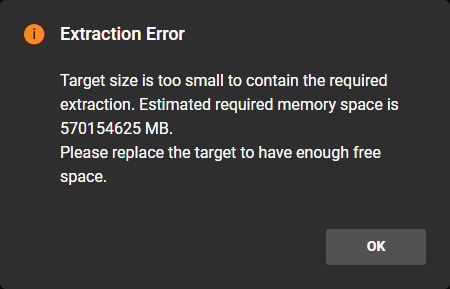

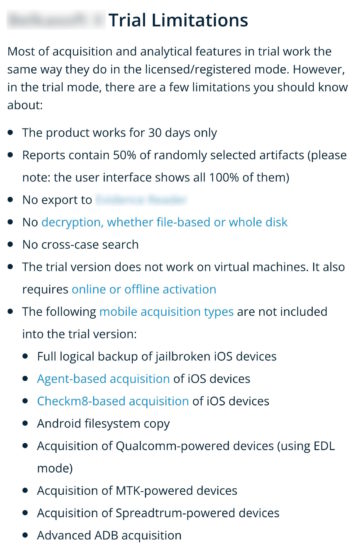

When it comes to trial versions — please note that they are often very limited; here is an example:

If you love something, set it free

Many (if not all) forensic products rely heavily on open-source code developed and maintained by the community. While this is generally acceptable, forensic vendors often fail to acknowledge the community projects they utilize. The contributions made to GPLv3 projects, such as those related to checkm8, are seldom acknowledged. The lack of recognition for the community’s work is concerning. A great example of this are the many checkm8-based extraction tools developed by various vendors. As a coincidence, most forensic vendors tout the same compatibility with checkm8 extraction methods as the checkra1n jailbreak does. To see our take on this issue, read iOS Forensic Toolkit and Open Source.

When marketing is king

Everything mentioned above in no way diminishes the merits of forensic products we’re talking about. They all possess the required functionality for unlocking, extracting, and analyzing digital evidence. Their speed and usability are impressive (although, of course, there is still room for improvement).

The problem lies in the fact that marketing and sales clearly take priority over research and development. In their pursuit of customers, manufacturers have started behaving rather unethically, concealing shortcomings and limitations (which inevitably exist) while significantly exaggerating capabilities. This “competition” is absolutely detrimental to the cause.

One thing we have not yet mentioned are bugs and issues. Unfortunately, some of these bugs and issues remain unaddressed for months, if not years. Manufacturers take advantage of their monopolistic position in certain markets and the fact that users have become accustomed to their solutions, making it difficult for them to switch to alternatives.

The truth is out there

There are a couple of things I wanted to outline. It is crucial to understand that there is no single software solution that can fully meet the diverse needs of the DFIR field. Relying solely on press releases and marketing materials is ill-advised. It is essential to verify and compare claims made by vendors. If a vendor refuses to disclose crucial information prior to securing a deal, it should raise concerns about their transparency and reliability. The truth lies beyond the marketing façade, and it is imperative to dig deeper to ensure the best outcomes.