Your browsing history represents your habits. You are what you read, and your browsing history reflects that. Your Google searches, visits to news sites, activities in blogs and forums, shopping, banking, communications in social networks and other Web-based activities can picture your daily activities. It could be that the browsing history is the most intimate part of what they call “online privacy”. You wouldn’t want your browsing history become public, would you?

“When I die, delete my browsing history”. This is what many of us want. However, if you’re an iPhone user, this is not going to work. Apple may hide your browsing history but still keep your records in the cloud, and someone (maybe using ElcomSoft tools) could eventually download your browsing history. How could this happen? Read along to find out!

The Sync

Apple can optionally sync many types of data across devices sharing the same Apple ID. Our tools can pull synced data such as phone calls, contacts, Safari tabs, browsing history and favorites from Apple iCloud. Extracting synced data is indispensable for mobile forensics as it can give access to up to date information that only arrived seconds ago – unlike cloud backups that are daily at best.

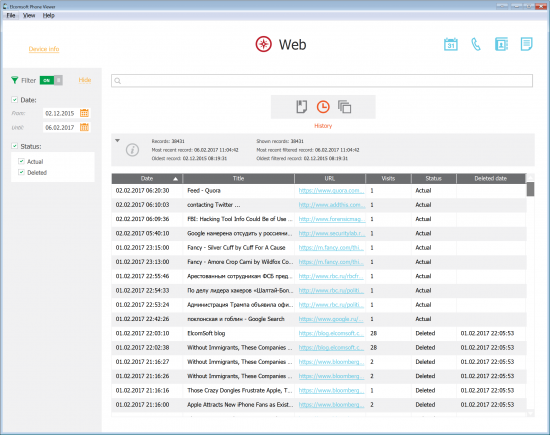

Our latest discovery concerns synced Safari history. While researching this sync, we discovered that deleting a browsing history record makes that record disappear from synced devices; however, the record still remains available (but invisible) in iCloud. We kept researching, and discovered that such deleted records can be kept in iCloud for more than a year. We updated Elcomsoft Phone Breaker to give it the ability to extract such deleted records from the cloud. Moreover, we were able to pull additional information about Safari history entries including the exact date and time each record was last visited and deleted!

Forensic Implications

Forensic use of synced data is hard to underestimate. Unlike cloud backups that are created daily at best, iCloud sync works nearly in real-time. Being able to track suspect’s activities almost no delay can be invaluable for surveillance and investigations.

Since deleting browsing history from iCloud is nearly impossible for the user, discovering illicit activities becomes much easier. Experts will be able to recover visits to extremist and other illicit Web sites even if the suspect deletes their browser history or wipes their iPhone.

iCloud Privacy Considerations

Apple has multiple privacy policies in place. In particular, the company promises not to keep information the user deletes from iCloud for more than 30 days. In the past, we found Apple to be somewhat lax about its privacy policies. At one time, we discovered that Apple were keeping deleted iCloud photos for much longer than the time period specified in their policy. On another occasion, we discovered that Apple syncs call information with their cloud servers, giving users no indication and no concise way to disable that sync. While many users disable iCloud backups for privacy reasons, those same users are commonly unaware of privacy implications that arise of those cloud syncs. Cloud synchronizations are rarely disabled as there is simply no clear way to do this. Moreover, disabling cloud sync would require disabling iCloud services, which has severe impact on device usability.

Things That Don’t Work

If Safari history is stored in the cloud, how can one get access to the records? One idea that doesn’t work would be setting up a new iPhone or iPad with the user’s Apple ID. While Safari browsing history will appear on the new device, the system will only bring the last 30 days of history – and no deleted records.

Another idea that doesn’t work would be using non-ElcomSoft forensic software for pulling Safari history from the cloud. Non-ElcomSoft tools present themselves as an iOS device or as a Web browser. This leads to the following consequences:

- These tools cannot access old browsing history records

- They cannot extract deleted records

- Finally, the user is alerted via an email notification that someone just had access to their cloud account (Elcomsoft Phone Breaker does not trigger this notification unless the user has Two-Factor Notification enabled, in which case a 2FA alert inevitably pops up).

Extracting Deleted Safari Browsing History

Safari history is synced across devices. Once you delete a record on one device, it will disappear on all other devices in a matter of seconds (or minutes), provided that those devices are connected to the Internet. While those records can be retained in SQLite database for technical reasons, a flush or cleanup will purge them sooner or later (on an actively used device, this can happen in a few days or up to 2-3 weeks).

However, those same records will be kept in Apple iCloud for much longer. In fact, we were able to access records dated more than one year back. The user does not see those records and does not know they still exist on Apple servers.

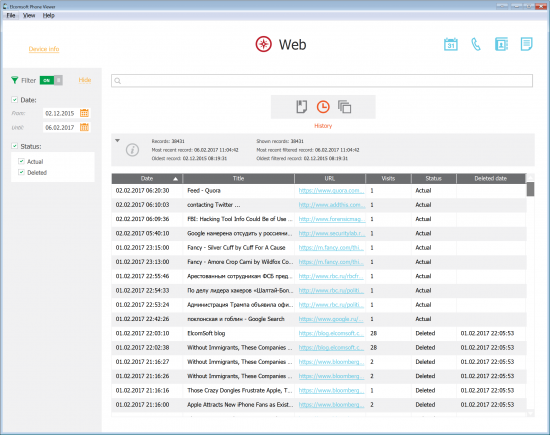

Elcomsoft Phone Breaker 6.40 can be used to extract those deleted browsing history records, while Elcomsoft Phone Viewer 2.25 is updated to allow filtering existing and deleted records.

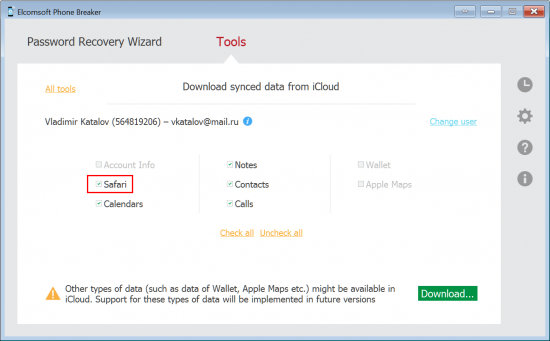

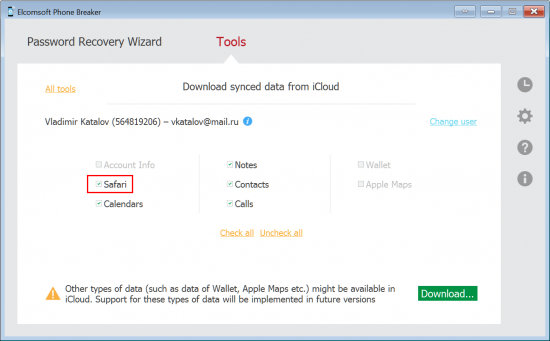

To extract Safari browsing history from iCloud, do the following:

- Launch Elcomsoft Phone Breaker 6.40 or newer

- Click “Download Synced Data from iCloud”

- Authenticate with Apple ID/password or binary authentication token

- Specify everything you’d like to download. Make sure to check “Safari”

- Wait for the download to complete

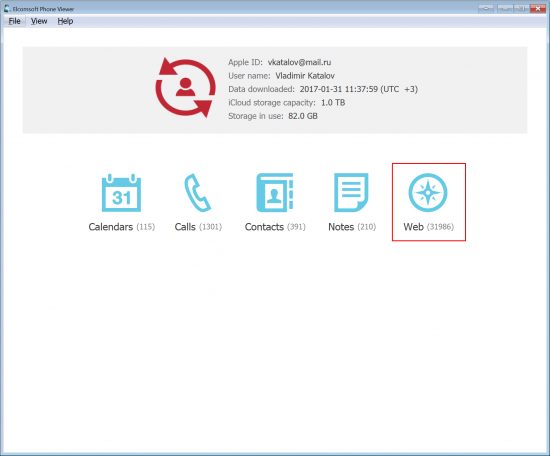

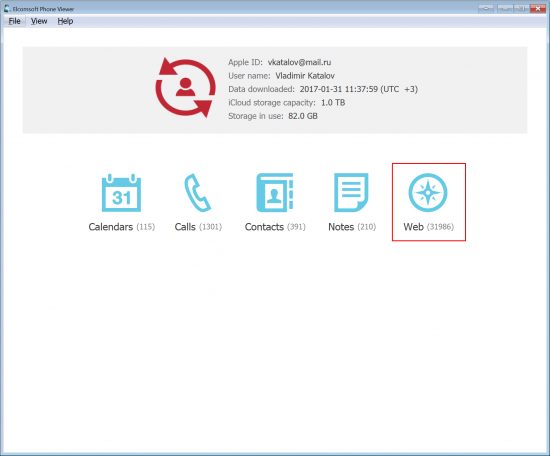

To view deleted Safari history records using Elcomsoft Phone Viewer:

- Launch Elcomsoft Phone Viewer 2.25 or newer

- Open iCloud synced data you downloaded

- Navigate to “Web”

- Optionally, apply filter to specify records for actual or deleted browsing history records.

Note: You’ll be also able to see the date and time on which the records were deleted.

Looking for a Password?

In order to extract Safari history from iCloud, you’ll need to authenticate into the user’s Apple ID. While you can use the login and password combination, sometimes you simply won’t know the password. If this is the case, you can use an authentication token extracted from the user’s computer.

Elcomsoft Phone Breaker comes with tools to help experts extract iCloud authentication tokens. These tokens are automatically created by iCloud Control Panel on Windows and Mac computers that were synced with iCloud. By using the token to log in, you’ll bypass both the password and the secondary authentication prompt if two-factor authentication is enabled on the user’s account. As a result, iCloud access alert will not be delivered to the user.

Update: we have informed media about this issue in advance, and they reached Apple for comments. As far as we know, Apple has not responded, but started purging older history records. For what we know, they could be just moving them to other servers, making deleted records inaccessible from the outside; but we never know for sure. Either way, as of right now, for most iCloud accounts we can see history records for the last two weeks only (deleted records for those two weeks are still there though).

Good move, Apple. Still, we would like to get an explanation.